Anti-Cinematic

Long yap about my dislike for modern "cinematic" culture that has risen from the new age of digital filmmakers, from the perspective of a young digital filmmaker instead of a boomer for once.

Seth Copela

5/18/20254 min read

Over the span of the last decade, the term cinematic has lost its meaning.

Once reserved for works that evoked the artistry, craft, and emotional weight of cinema, the word has been cheapened, misused, and reshaped by a generation of new creators who, while innovative and talented, have been misled by trends, marketing, and convenience.

For much of cinema’s history, film technology remained out of reach for the general public. Filmmaking was an exclusive craft, dictated by access to expensive gear, teams of skilled professionals, and industry infrastructure. Cameras and lenses were costly. Lighting, sound, and post-production tools were industrial in scale and price. If you wanted to make a film, you needed resources, training, and immense means to do so.

But over the past 20 years, that dynamic has shifted drastically. The rise of accessible, consumer grade gear and its rapid improvement, has democratized the medium. In today’s world, you can purchase a cheap mirrorless camera & lens for a few thousand with full frame capability, record pristine 10-bit 4K footage, then color grade it in your bedroom using software that was once reserved for Hollywood studios. Filmmaking is no longer an elitist pursuit of the rich. The huge barrier to entry has been gradually dropped, and in its place a tidal wave of new creators; YouTubers, TikTokers and indie filmmakers have emerged, myself among them.

This explosion of creativity has had profound effects, both good and bad, which I will cover in the rest of this blog.

My problem with the word “Cinematic”

The influx of new talent into this industry has stirred up confusion around certain terminology, most notably, the word cinematic. Once used to describe the specific qualities that define traditional cinema, such as thoughtful composition, dramatic lighting, immersive sound design, deliberate pacing and emotional resonance. The word has been diluted into something much more superficial and empty.

In the age of YouTube, cinematic has become a buzzword. Everywhere I look I see tutorials that promise “cinematic looks” in ten minutes. Gear reviews claim a camera can “instantly make your footage cinematic.” LUT packs are marketed as the one-click solution to “cinematic color.” As a result, cinematic is now often equated with shallow depth of field, widescreen aspect ratios, orange-and-teal grading, and soft bloom filters.

Many believe that to achieve a cinematic look, all one needs is a good lens, a color grade, and perhaps a little grain and halation. Completely ignoring the complex and nuanced elements that truly make cinema what it is: storytelling through image, sound, performance, and design.

True cinematic work is holistic. It’s not just a camera or a LUT. It’s the culmination of choices across the entire production pipeline. Direction, set design, lighting, sound, wardrobe, makeup, acting, editing, and sound mixing to name just a handful of the steps in making a film. And to reduce all of that to just a color preset is not only reductive, it’s just straight up misleading.

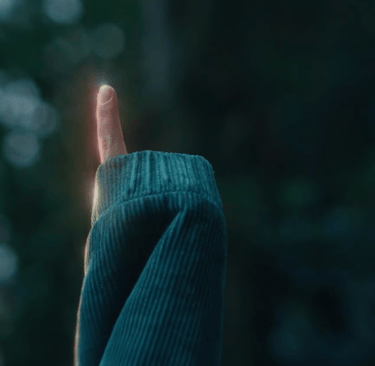

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE

ANTI-CINEMATIC

My post content

TEAL

&

ORANGE

Social Media

While platforms like YouTube have democratized education and empowered countless creators, they’ve also propagated a culture of shortcut artistry. This environment often rewards aesthetics over substance, trends over technique. A new generation of creators is being raised on tutorials that treat cinematic like a filter you can apply, rather than a discipline you must study.

This has lead to a flood of poorly executed work labeled as cinematic: poorly lit footage, crushed blacks, overexposed highlights, heavily saturated midtones, and color grades that push hues into unnatural extremes.

One color trend I have slowly become to despise is the all so common “cinematic” Teal & Orange. Skin tones look sickly, whites become creamy or blue, and bloom effects are applied so heavily that scenes lose all contrast and clarity. Grain is often added not to evoke a feeling, but to simulate a nostalgia the creator hasn’t yet understood.

The Good

Despite the misuse of terms and techniques, it’s important to recognize the good. This creative boom has also brought a much-needed breath of fresh air into the industry. With more voices and fewer gatekeepers, we’re seeing bold experimentation and new innovative storytelling methods. There are creators whom are making stunning short films with minimal budgets, and filmmakers who never went to film school producing festival-worthy work from their basements.

This new age of filmmakers should absolutely be embraced. They’re redefining cinema in exciting ways and expanding its reach. But as a community, we need to be vigilant. We must ensure that newcomers aren’t falling into the trap of shallow aesthetics and misplaced terminology. Proper education, mentorship, and honest critiques are vital to nurture this generation. The goal isn’t to gatekeep, but to guide and to help rising filmmakers understand that cinematic isn’t something you can download. It’s something you craft.

The misuse of the word cinematic is more than just a linguistic gripe. It represents a deeper issue in how we understand, teach, and practice the art of filmmaking. When new creators are led to believe that cinematic is something achieved solely through gear or color presets, it fosters disillusionment, stagnation, and miscommunication.

This isn’t a lament for the past, nor a rejection of the new. It’s a call to responsibility. The next generation of filmmakers isn’t the problem, but they deserve better guidance. Let us celebrate this era of creative freedom while remembering that cinema is, and always will be, more than just a look.

Seth.